Hennepin County’s new $20 million Youth Stabilization Center represents a critical acknowledgment of a long-ignored reality: our system has catastrophically failed children with complex mental and behavioral health needs. While this 13-bed facility marks a significant step forward, it also reveals the profound depth of our societal failure to address youth mental health crises before they escalate to emergency levels.

For years, vulnerable children as young as 8 have languished in emergency departments or inappropriate detention facilities—environments that exacerbate trauma rather than heal it. The county’s investment signals a belated recognition that criminalizing mental health crises creates devastating consequences for children whose developing brains and identities are permanently shaped by these experiences.

A Necessary But Woefully Inadequate Response

The creation of this stabilization center addresses a critical gap in the continuum of care, but the facility’s limited capacity—just 13 beds plus 4 withdrawal management spaces—highlights the massive disconnect between need and resources. When Commissioner Edelson described the situation as a ‘crisis for our county,’ she wasn’t exaggerating. The $7 million annual operating cost reflects the intensive staffing and specialized care these youth require.

Consider the mathematics: Hennepin County has approximately 287,000 residents under 18. National data suggests that about 22% of children have mental health conditions requiring intervention. Even if just 1% of those youth experience severe crises annually, we’re talking about hundreds of children potentially needing this level of care—yet the facility can serve barely a dozen at a time.

The Milwaukee Wraparound program offers an instructive comparison. Launched in the early 2000s, it initially focused on intensive community-based alternatives but discovered that without adequate crisis stabilization facilities, youth continued cycling through emergency departments and detention. When they added stabilization beds proportional to their population (approximately 1 bed per 25,000 youth), outcomes improved dramatically.

Addressing Root Causes Requires Systemic Change

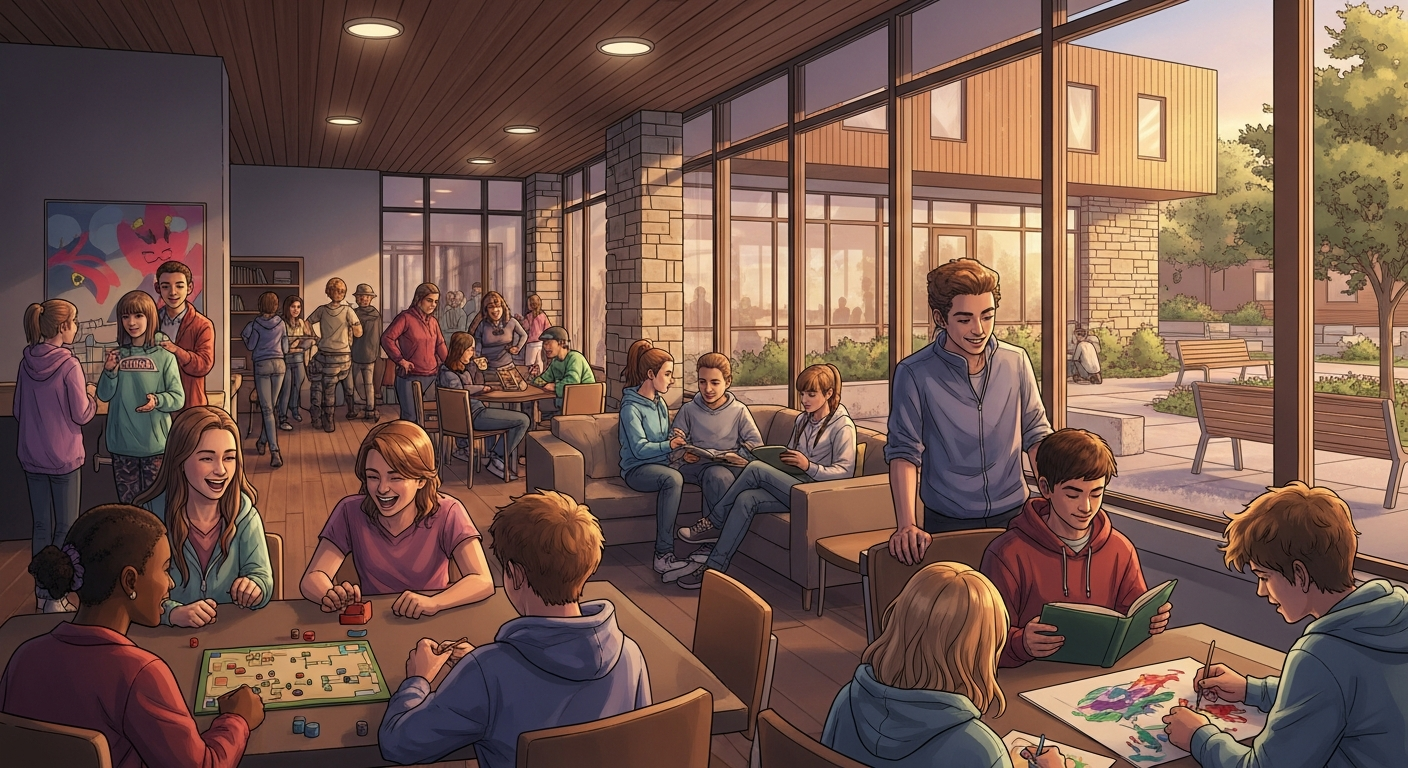

While the center’s home-like environment represents best practices in trauma-informed care, we must confront uncomfortable truths about why children reach such severe crisis points. The county’s approach focuses on the critical moment of crisis but does little to address the systemic failures that create these emergencies.

Research from the Child Mind Institute shows that most children exhibit warning signs of serious mental health conditions 2-4 years before reaching crisis levels. Yet our fragmented healthcare system, with its arbitrary distinctions between behavioral and physical health, creates nearly insurmountable barriers to early intervention. Insurance limitations, provider shortages, and stigma compound these challenges.

The Massachusetts Children’s Behavioral Health Initiative offers a compelling alternative model. After a class action lawsuit forced systemic reform, Massachusetts implemented universal behavioral health screening in pediatric settings, created mobile crisis teams, and established a legal right to intensive home-based services. The result? Emergency department boarding for youth in crisis decreased by 40% within five years.

The False Economy of Underfunding Prevention

The $20 million facility cost and $7 million annual operating budget represent significant investment, but economic analyses consistently demonstrate that early intervention delivers exponentially greater returns. A RAND Corporation study found that every dollar invested in evidence-based prevention and early intervention programs for youth mental health returns $7-$30 in reduced costs to healthcare, criminal justice, and education systems.

Consider that a single year of juvenile detention costs approximately $150,000 per youth. Emergency department boarding can exceed $2,000 per day. These astronomical costs dwarf the expense of comprehensive school-based mental health services, which average $250-500 per student annually when implemented system-wide.

The Centennial School District in Pennsylvania implemented a comprehensive K-12 mental health framework with universal screening and tiered interventions. Their initial investment of $1.2 million annually resulted in a 67% reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations and 82% fewer juvenile justice referrals within three years—saving an estimated $3.8 million in crisis services and improving educational outcomes.

Alternative Viewpoints: Is Institutionalization the Answer?

Some critics argue that creating specialized facilities risks returning to an era of institutionalizing troubled youth rather than supporting them in community settings. This concern has validity—the history of residential treatment is rife with examples of abuse, neglect, and iatrogenic harm. Studies show that many youth emerge from residential settings with additional trauma and disconnection from natural support systems.

However, this criticism misunderstands the purpose of short-term stabilization. The Hennepin facility explicitly positions itself as a transitional setting—a place to pause, assess, and connect youth with appropriate longer-term supports. When implemented correctly, stabilization centers serve as bridges to community-based care, not replacements for it.

The more substantive critique concerns whether the county has invested sufficiently in the community-based services these youth will need after stabilization. Without robust follow-up care, including intensive in-home services, specialized educational supports, and family therapy, the stabilization center risks becoming merely a revolving door.

Moving Forward: From Crisis Response to Crisis Prevention

Hennepin County deserves credit for acknowledging the emergency and investing in this solution. The facility’s design reflects current understanding of trauma-informed environments, and the partnership with Nexus Family Housing brings critical expertise in supporting youth with complex needs.

However, true progress requires expanding our vision beyond crisis response. The county must pair this investment with equally robust funding for early identification and intervention. This means implementing universal mental health screening in schools, expanding the mental health workforce through innovative training programs, and removing financial barriers to accessing care.

Most critically, we must recognize that youth mental health crises don’t occur in isolation from other social determinants. Housing instability, food insecurity, community violence, and systemic racism all contribute to the deterioration of children’s mental health. Any comprehensive solution must address these factors through coordinated, cross-system approaches.

The Youth Stabilization Center represents an important acknowledgment of our collective failure and a commitment to do better. The true measure of its success will be whether it catalyzes the broader systemic changes necessary to ensure fewer children ever need such intensive intervention.